Talking about animals that hibernate is a great way to get kids thinking about the behaviors and adaptations that help animals survive in their climates. Learning about a variety of animals that use hibernation to survive builds kids’ background knowledge and can dispel myths. (Spoiler: Hibernating isn’t the same as sleeping!) Learn more about hibernation and check out 12 interesting animals that hibernate below.

Plus be sure to grab your free hibernation worksheet bundle by filling out the form on this page.

What is hibernation?

Animals hibernate to conserve energy. Conserving energy helps these animals survive when food and water are scarce. (Most famously, animals hibernate during cold winter temperatures, but scientists have more recently learned that some animals hibernate in summer to withstand the extreme heat; this is called “estivation.”)

Animals that hibernate are not just asleep. During sleep, normal functions continue at a resting rate. According to National Geographic, hibernation is an extended state of “torpor.” Torpor is when an animal’s body temperature cools, allowing its metabolism—the rate at which its body uses energy—to slow to less than 5% of normal. This means hibernating animals slow their heartbeat, breathing, and other bodily functions way down. Brain activity drops to almost none. Plus, to answer the question a student is sure to ask: While in torpor, animals don’t even go to the bathroom!

Hibernating animals do come out of their torpor periodically, bringing their temperature, heart rate, and breathing closer to normal for a bit. Scientists are still trying to figure out why. (Weirdly, some animals use these arousal periods to sleep!)

Researchers study hibernating animals’ behavior patterns, brain chemistry, and genes to learn more about how and why they hibernate. There’s even hope that this research could be applied to humans one day. To learn more, watch the TED-Ed talk “How Does Hibernation Work?”

Animals that undergo hibernation, brumation, and diapause

Animals’ hibernation behavior can vary, so it’s fun to learn about a variety of animals that hibernate. From teeny-tiny mice to the giant black bear, here are some favorite animals that hibernate to teach your class about.

Technically, only warm-blooded animals hibernate. Cold-blooded animals can undergo a similar slow-down called “brumation.” When insects go into a dormant state, it’s called “diapause.” We’ve included examples of each of these on our list so you can talk with students about them too!

1. Groundhog (Hibernation)

Also called woodchucks, groundhogs feed heavily on green plants and fruits in summer to store fat. Then, they hibernate starting in late fall for up to 150 days. The National Wildlife Foundation’s fact sheet on groundhogs states that during hibernation, they curl up into a ball and drop their body temperature to as low as 37 degrees Fahrenheit. Their breathing slows to around two breaths per minute. Groundhog Day on February 2 has some scientific basis: Some males emerge from hibernation around that time to scout out nearby burrows of female groundhogs.

2. Arctic Ground Squirrel (Hibernation)

While most squirrels don’t hibernate, arctic ground squirrels are hibernators. These cold-dwelling diggers spend their active summer months creating mazes of underground burrows and tunnels in the Arctic region. The National Park Service reports that ground squirrels hibernate as soon as they’ve eaten enough to build up their fat stores, as early as August. This means they spend a whopping seven to eight months in hibernation. Their claim to fame is how cold they get. Their body temperature dips to the lowest temperature ever recorded in a mammal, below freezing. Every few weeks, they shiver and shake to briefly warm themselves to their normal temperature, then return to their frigid state.

3. Meadow Jumping Mouse (Hibernation)

Most species of mice don’t hibernate, though they may go into torpor for parts of the day to save energy in very cold temperatures. However, the meadow jumping mouse, and its relative the woodland jumping mouse, are true hibernators. According to the University of Michigan, they are known for having long tails and long back feet and prefer grassy areas near water. To hibernate during winter, meadow jumping mice burrow 1 to 3 feet belowground and make grass nests.

4. Little Brown Bat (Hibernation)

Bats deal with cold temperatures by migrating, hibernating, or both, depending on the species. It used to be common for little brown bats to hibernate in very large colonies of thousands of bats, typically in caves. Bat Conservation International reports that a fungal disease called white-nose syndrome has depleted the little brown bat population. Now, those extra-large hibernation parties aren’t as common. Hibernating bats usually arouse themselves every few weeks, but in their deepest torpor, they might go half an hour without taking a breath!

5. Fat-Tailed Dwarf Lemur (Hibernation)

These critters from Madagascar are the only primates that hibernate, and they have a special adaptation to make it work. They store up to 40% of their body fat in their tails. They burn this fat while they hibernate for up to seven months. Like other hibernating animals, their metabolism briefly goes back to normal every so often, then drops again. Learn more about lemurs at the Duke Lemur Center.

6. Bear (Hibernation)

Bears might be the most famous hibernators of all, but they don’t follow all the same behavior patterns as smaller animals. Smithsonian magazine reports that bears’ extra-warm coats mean they don’t lose as much body heat, so their temperature doesn’t drop as drastically as other animals. This means they don’t need to arouse from their torpor to warm up like other animals do. They do, however, get up and move around sometimes in their slowed-down state. Mama bears can even give birth while hibernating! The babies snuggle up until spring.

7. Common Poorwill (Hibernation)

The common poorwill is the only known hibernating bird. The National Audubon Society shares that when faced with cold temperatures and food shortages, this bird can go into torpor for days or weeks at a time. The Hopi tribe’s name for this bird means “sleeping one.”

8. Hedgehog (Hibernation)

Hedgehogs aren’t native to North America, but different types live in Europe, Asia, and Africa. They hibernate to survive the temperatures and lack of food in cold climates. These cuties find a cozy spot in a pile of leaves or under a structure and curl into a little ball to enter torpor. They do wake up sometimes, as other hibernating animals do, and might even use this time to find a new nest to snuggle back down in.

9. Garter Snake (Brumation)

Snakes are cold-blooded, which means their temperature changes with their surroundings. Cold-blooded animals that live in wintry climates, like garter snakes, do something very similar to hibernating: They brumate. Instead of using stored fat for energy like hibernating animals do, animals in brumation use glycogen (stored sugar) to stay alive while their bodies slow way down. Snakes often brumate in underground dens, below the frozen layer of soil. According to Discover magazine, garter snake dens might house up to 20,000 snakes. Yikes!

10. Wood Frog (Brumation)

Frogs are cold-blooded amphibians, so they use glycogen (stored sugar) to stay alive when their bodies slow down into brumation to survive cold temperatures. Wood frogs can get especially chilly. Scientific American explains that during brumation, a wood frog stops breathing and its heart stops beating. The glycogen in its body acts like antifreeze so its organs stay safe. So, even in freezing temperatures, wood frogs tucked away in cracks between rocks or under leaves don’t die. As temperatures warm up in the spring, they slowly thaw out.

11. Painted Turtle (Brumation)

Like many other turtles found in northern climates, painted turtles survive the winter by burrowing under mud or frozen water and going into brumation—slowing their metabolism way down for the winter months. In brumation, they can survive winter without food or coming to the surface for air, according to the University of Minnesota. They get the small amounts of oxygen they need from the water, through a process known as cloacal respiration. This is basically breathing through their rear ends. If you’re brave enough to discuss it with your class, PBS NewsHour has some more information on turtle “butt-breathing”!

12. Bee (Diapause)

Bees lower their metabolism to enter diapause (the insect equivalent of hibernation) and stay in their nests to survive winter. The state they “pause” in depends on when they were born. Bees born in spring will already be adults, while bees born in fall will be “prepupae” who haven’t even left the nest yet. Organizations that focus on protecting pollinators, like the Tufts Pollinator Initiative, encourage people to plant fall-blooming native plants so bees can fuel up on nectar before winter, and leave piles of leaves as shelter for nests. If bees don’t stay safe in their nests during cold weather, they will die.

Get Your Free Hibernation Worksheet Bundle

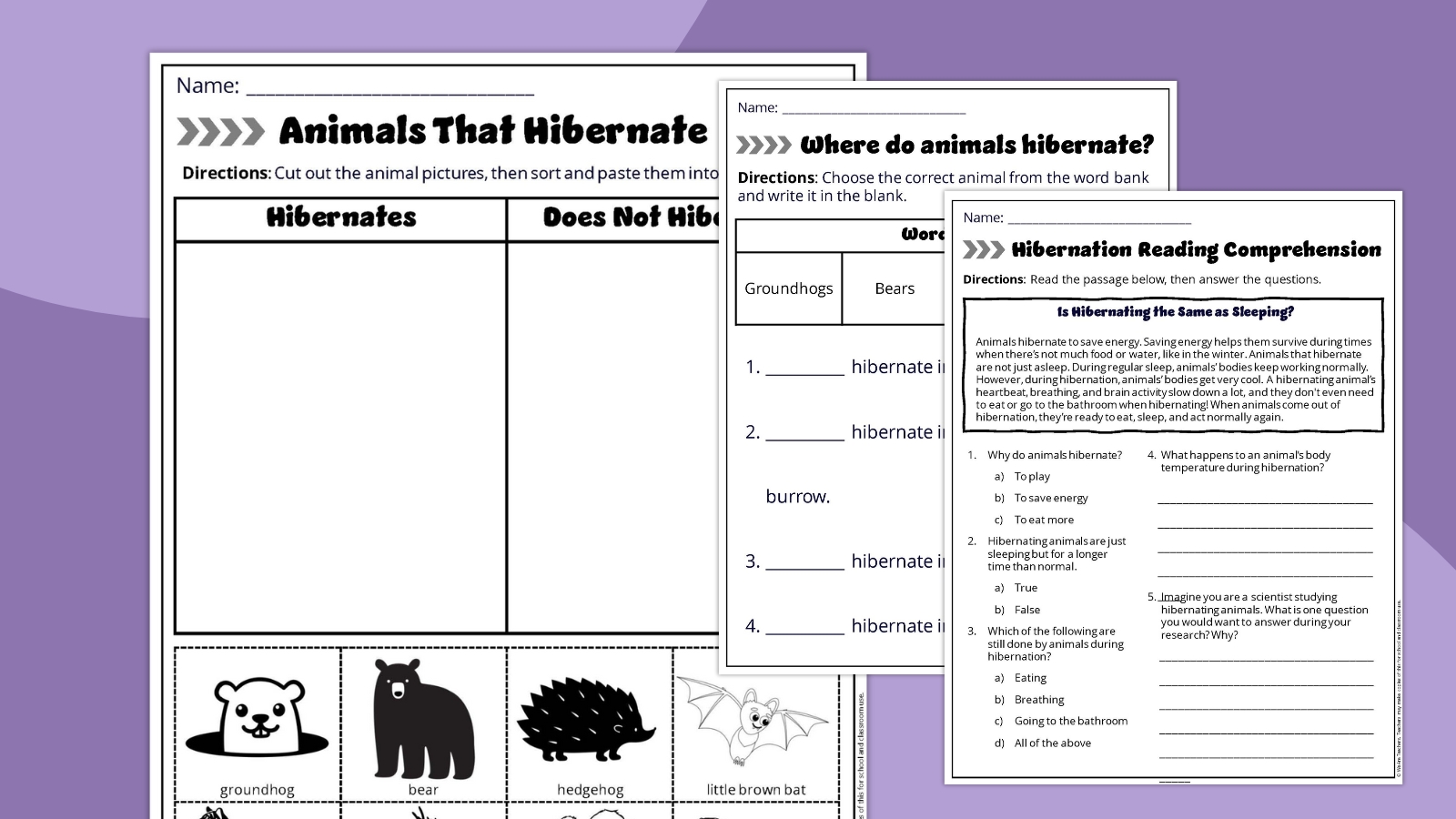

Want to make teaching hibernation fun and easy? Just fill out the form on this page to get your free hibernation worksheet bundle. You’ll get:

- Cut-and-sort activity

- Fill-in-the blanks worksheet

- Reading comprehension passage and questions